Inside the Zone Rouge on Vimy Ridge

The preserved and forbidden grounds of Canada's most iconic battlefield

Vimy Ridge is perhaps the most iconic First World War battle for modern day Canadians. For visitors to the site, the preserved Vimy Ridge battlefield provides a fascinating glimpse into what it might’ve been like to be there 100 years ago. Access is quite limited however for safety reasons but also to ensure the perseverance of the battlefield. According to French sources, each year anywhere from 300,000 - 600,000 tons of unexploded ordinance are recovered from the First World War battlefields in France & Flanders. From German stick grenades, to stokes mortars, and even 9.2 inch shells, nothing is unheard of on this part of the Western Front. Even after a century of the guns falling silent and where life has seen to move on in most places, Vimy still holds some risks. Footpaths have been established to provide visitors a safe and regulated passage to some of the sites, and herds of sheep are used to cut the grass. The grounds are impeccably maintained but is a far cry to what it would’ve looked like during the war. Although you can from the paths you can still see many of the trenches, bunkers and craters, Vimy Ridge is somewhat of an iceberg; with approximately 10% of the area being accessible and the other 90% classified as the Zone Rouge (Red Zone) and thus off limits to the public. In July 2022, I conducted an authorized site visit to the Zone Rouge on behalf of the Loyal Edmonton Regiment Museum with Vimy Ridge Memorial Park site director John Desrosiers to view a section of this hidden and seldom seen battlefield.

Upon first entry into the Zone Rouge, it becomes apparent you are stepping into a different world. Although the battlefield is heavily forested now with thick overgrowth shrouding much of the scars of battle, as soon as one steps off the main access road, it is unbelievable what could still be observed. With trenches and shell craters appearing at every step, and mine craters every couple steps, all untouched and likely never seen since the last soldier left in 1918. Not clean and serene like how most visitors will see Vimy Ridge, the Zone Rouge is rugged. Nowhere near as rugged as what the soldiers experienced, but the thick thorn bushes and the hundreds of shell holes that interrupt every step give perhaps some insight into how difficult it was to traverse such ground even without being shot at. Although the big attack of the 9th of April is now synonymous with Vimy Ridge and the reason most people make the pilgrimage, I was drawn to the battlefield for a different and much smaller action which took place at a place named the Chassery Crater in late January 1917. Seeing 21 members of the 49th Battalion (Edmonton Regiment) conducted a very successful trench raid, securing several prisoners and dishing great damage out to the enemy’s defenses and garrison all within a span of 15 minutes and with virtually no casualties sustained on the part of the raiders. As an experienced First World War battlefield traveler, with a great passion for the history of the 49th Battalion in particular, it had been a long time dream of mine to see where it had all taken place with my own eyes. Now within the Zone Rouge and after scouring through the maze of trenches and shell holes, and each step getting closer and closer to the destination, we eventually reached the famous crater line at Vimy. Evidence of mine warfare where either side tunneled beneath their adversaries trench systems before packing the galleries full of explosives and detonating them. The blasts vaporized men into oblivion and erased the trenches off the face of the earth. By the time the Canadian Corps had arrived here in the late autumn of 1916, the allied frontline ran along one lip of the craters and on the opposite lip, sometimes as little as fifty yards away, were the Germans. One can only imagine the constant fear the soldiers holding the trenches here had knowing a mine could be blown any moment. These craters characterized no man's land in this sector and still to this day symbolize where the armies of two powerful empires collided and dug in more than a century ago.

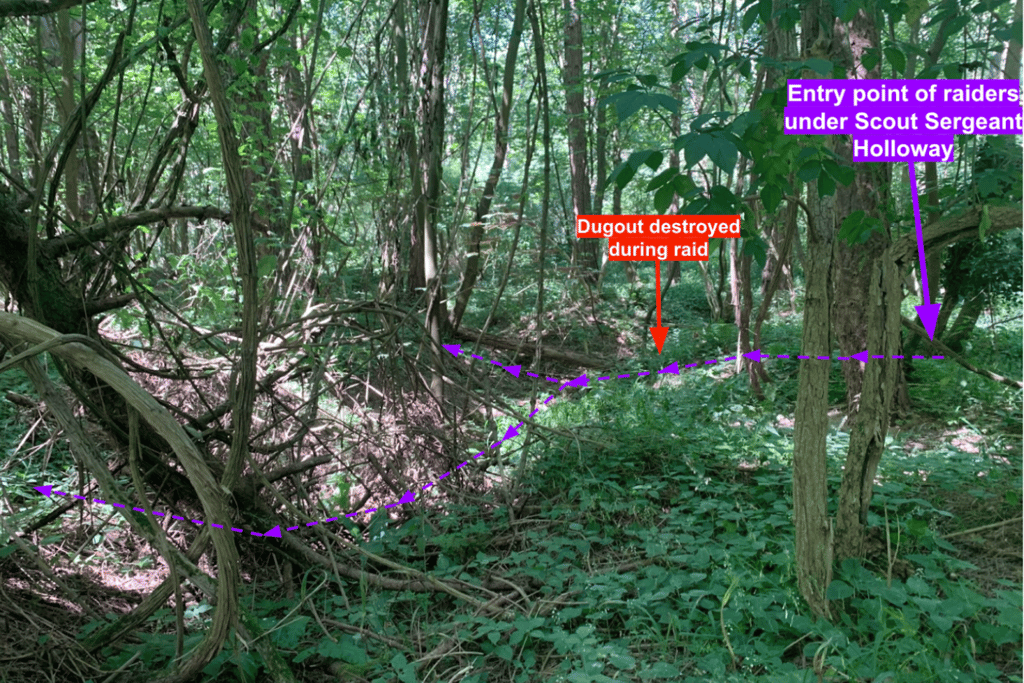

Skirting across the lips of these craters, we eventually arrived at the so-called ‘Chassery Crater’. With only a sketch map from the unit's war diary to guide us, we followed the arrows indicating the movements of the raiders. Working our way along the Northern lip of the Chassery Crater, we were now following in the footsteps of the raiders of 1917. Half way across no man's land, the 49th Battalion raiders had split up into two groups and thus gained entry into the German lines at two separate locations. Following the route of the first group, we entered the German trenches at the exact spot they had, and for them, action was not far away. Within a matter of steps we came across the first post where Germans were recorded to have first been encountered by the raiders. Where we now found ourselves was where no less than three German soldiers had been killed. Continuing on not much further on, we came across where the next post had allegedly been located, and where a further two Germans were killed and the last, taken prisoner. Returning back on ourselves and following the sketch map at hand, we traversed down what was once a communication trench and eventually reached the T-junction as was shown on the map. Stopping here and glancing to my left, I was now looking at where the other half of the raiding force led by Scout Sergeant Holloway gained entry into the German trenches, and to my immediate right was a slight yet noticeable indentation on the wall of the trench. Consulting my notes, it became apparent that this was once a dugout which had been destroyed by the raiders. In 1940, Scout Sergeant Holloway published an account of the raid in the 49th Battalion’s magazine ‘The Fortyniner’. Included in this detailed narrative was his encounter with this exact dugout; “I pulled the pin from a Mills bomb, and first letting the spring fly so there could be no question of it being thrown back, I tossed it down the steps, and others of the party dropped other surprise packets for any Germans who might be inside. Then I hurried on after several men who had passed me and came upon a German post of three men, one of whom was lying dying on the ground.”

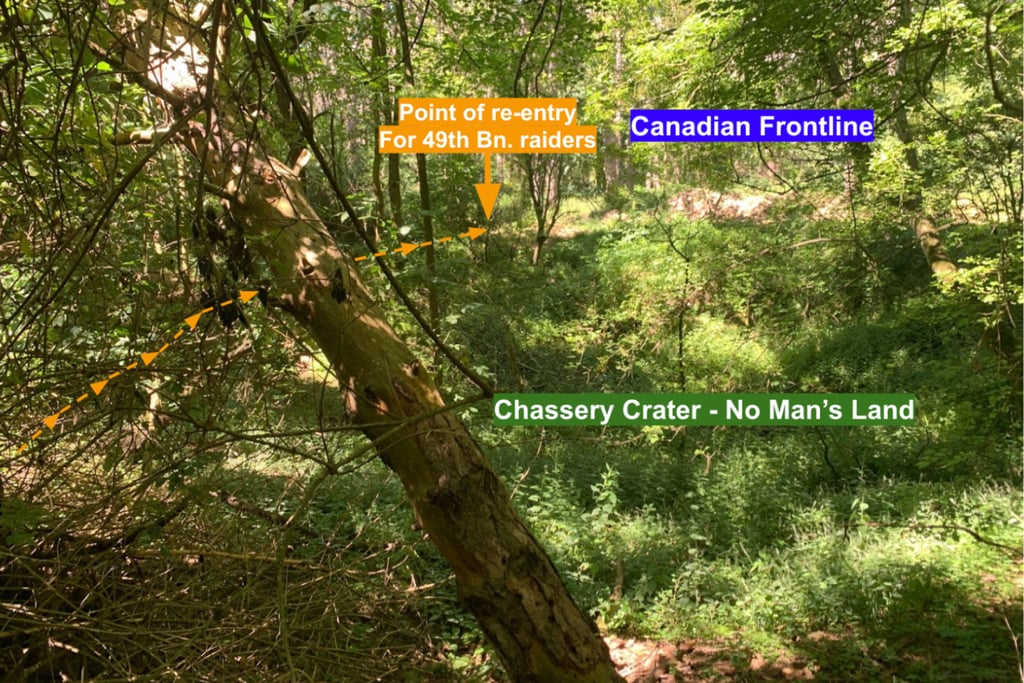

Moving along the winding twists and narrow turns, we eventually reached the point where the two 49th Battalion raiding parties met. Here, six Germans were cornered and annihilated by the Canadians. Returning back to the lip of the Chassery Crater and looking out to my left, was a peculiarly long and narrow mine crater. A so-called Wombat Mine as explained by John Desrosiers. This mine had been blown on the first day of the Battle of Vimy Ridge on the 9th of April 1917. to serve as a sort of instantaneous communication trench linking the newly captured German frontline with the Canadian jumping off line. In this sector, it was the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles from British Columbia who went into action that day. To my front, I could see the Canadian frontline not more than 60 yards away. This is where they would have gone over the top that morning but also where the 49th Battalion raiders would have returned to on that frigid morning in January 1917, with both prisoners and souvenirs in hand.

The head of a German stick grenade and the ‘Wombat Mine’ detonated 9/4/1917. All evidence of the heavy fighting here during the First World War.

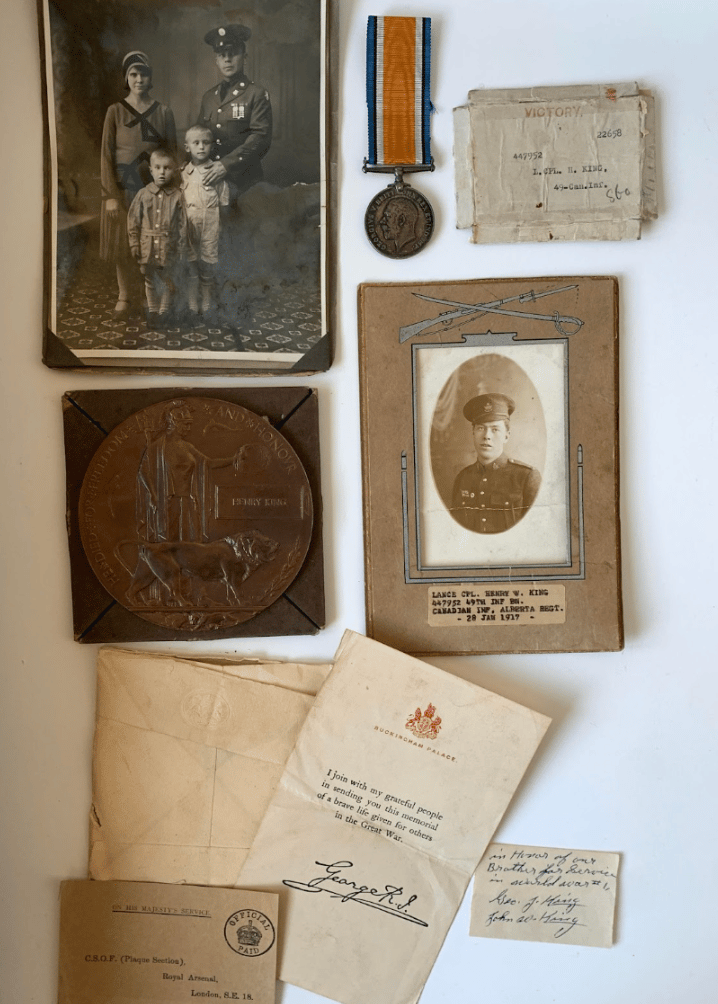

Although being a successful raid, it did not come without its cost. Later in the day, the Canadian frontline on the Chassery Crater was heavily shelled by German artillery and trench mortars. Tragically, three men from the 49th Battalion who were occupying the trench were killed in this barrage: Lieutenant Jellett, Private Eaton and Lance Corporal King. I was recently offered the medals and ephemera belonging to the latter named soldier and was very pleased to have acquired the group into my collection. An American with previous experience in the US Army, Henry King enlisted in Calgary in late 1915 and arrived as a reinforcement to the 49th Battalion near Ypres in May of 1916. Within a week, he was thrusted into his first battle at Sanctuary Wood, where he was reported slightly wounded. Despite his wounds, Henry King served continuously in the Ypres Salient, the Somme and finally Vimy Ridge until his death on the Chassery Crater, aged 25 years old. As a collector of the 49th Battalion, acquiring a group related to a small action like The Chassery Raid is always exciting. But of course it is much more than just ticking off a want from the militaria want list. These artifacts carry with it a great meaning of remembrance. It is unlikely the family of the Henry King was ever able to make the trip to visit his grave in France, and it was instead these artifacts that retained the enduring memory of their late son, brother, or uncle. During a more recent trip to the battlefields in November 2022, I had the privilege of visiting Lance Corporal King's grave in Ecoivres Military Cemetery, Mont St. Eloi. As the current bestowdien of his estate and with it, perhaps the final material connection to this soldier, it was a most fulfilling experience and connection to make this pilgrimage and pay my respects.

The seldom seen battleground in the Zone Rouge is perhaps the most incredible section of battlefield on the British sector of the Western Front. It is a place where time has stood still and with countless stories to be told at every twist and turn in that forest. For the late CEF veterans that in the post war years returned to what is now the Zone Rouge at Vimy; “Each spot rushe[d] back, vivid, realistic (memories), so that old duckwalks appear as if by magic and you look eagerly for a wisp of smoke at the place where the cooks were established. Suddenly you are remembering that a dugout was just here. There is no trace of it, but you are certain. Enquire, and you will be told that the entrance was filled in because it was unsafe and so many ardent tourists will not heed warnings. Then you remember the night you helped carry Jim or Bill or Davy down that Communication Trench, and a lump comes to your throat. It’s strange to be here” (Will Bird MM, 1932). Although for myself, I found it most strange to leave the Zone Rouge. In a landscape still engulfed by war, one truly felt a divine connection to the soldiers of that war and to suddenly leave and escape the Zone Rouge and return to the modern roads, cars and the beautifully manicured grounds surrounding the Vimy Ridge National Memorial all seemed a far cry to the untamed and authentic battlefield I had just been traversing through. Once inside the Zone Rouge, it becomes grossly apparent to the visitor that this isn’t a hollywood movie set. Every trench was dug by a real soldier and ever crater spawned by a real explosion and the visitor knows very well of the dark secrets and men that are likely just inches below the surface. It would’ve been a hive of activity here in 1917, but now it is quiet. Gone are the booms of the guns, the squeals of the wounded and dying, the incessant rain and the wrath of machine gun bullets. But it all seems that much closer in a landscape unchanged and untouched; where the famous First World War saying “C’est la guerre” seems most applicable today as it was then. Some places never change, and I hope the same will hold true for one of the final pockets of untouched Canadian First World War battlefield. The Zone Rouge at Vimy Ridge.